Bronze statuette of a Spartan soldier found in Messinia The oldest traces of human habitation in the area around Kalamata date from the Proto-Helladic period (2600-2300 BC) and have been found at Akovitika, 2-3 kilometres northwest of Kalamata. Traces of ancient settlements have also been found at the hill of Tourla. Ancient Pharai was built later and was an important center during the Late Helladic (Mycenaean) age (1580-1120 BC.). The invasion of the Dorians (1100 BC) led to the decline of Pharai in favor of Dorian Thuria (Ellinika), northwest of Pharai. Pharai’s advantageous position as a way-station between Pylos and Sparta and the fertile soil of the Messinian plain were the reasons for the four Messinian Wars that took place between 743 and 459 BC. The victors in these wars were the Spartans, although they sustained heavy losses. The region was therefore dependent on (and settled by colonists from) Sparta, particularly between the Second Messinian War (640-620 BC) and the liberation of Messinia and the foundation of Messine (369 BC) by the Theban general Epaminondas.  Clay seal (Akovitika) Nevertheless, it continued to be administered by Laconians, therefore it repeatedly changed hands according to which side prevailed at any given time. In 292 BC during the Corinthian war, the Athenian admiral Conon and his ally, the Persian satrap Pharnabazus, sailed into the port of Pharai (only accessible in summer), according to Strabo. They looted the city whose inhabitants followed the Spartans into the battlefield, but afraid of losing their wheat crop and of the fact that the port was not secured, left for Finikounda.  Bronze statuette of a sea horse (Akovitika) A few decades later, Philip II of Macedon granted the region to the Messinians after the battle of Chaironeia (338 BC). Antigonos II Doson, did likewise after the Battle of Sellasia (222 BC) as did the Roman general Mommios, after the Roman conquest of Greece (146 BC), and the Roman Senate in 136/5 BC. Meanwhile Pharai was a member of the Messine commonwealth until it was dissolved in 182 BC, when an alliance was made with the Achaean commonwealth. Roman conquest

After the Roman conquest of Greece, Pharai became part of a federated state with Messine as its capital, although it was not yet completely free of claims from Laconia. Octavius Augustus granted Pharai to the Laconians after his victory at Aktio (31 BC), thereby punishing the Messinians for siding with Antony and Cleopatra.  The oldest traces of human presence in the area have been detected in Akovitika. Later however, Emperor Tiberius (14-37 AD) restored Pharai, Thuria and the region of Dentheleatis to the Messinians. The final delineation of its borders was made under Vespasian (78 AD). During the Hellenistic and Roman periods, Pharai was at its peak. Its importance was emphasized in two letters from the Emperor Commodus (177/8 AD) to the people of the city, carved on a stone column, parts of which have been preserved, when Pausanias visited the city in the second century AD, Pharai was just 1,000 meters from the sea and about 13 kilometres from ancient Avia (today’s Paleohora). A similar report was made by Strabo (first century AD) who placed it alongside the mouth of the Nedon River, whose banks have radically altered the landscape. In Pausanias’ time, the town that had spread around the fortress was in decline, in contrast to neighbouring Thuria. Therefore Pausanias saw only two temples there, one dedicated to the herohealers Nicomachus and Gorgasus, the sons of Machaon and Antikleia, the other to the goddess Tyche. Pausanias also visited the sacred wood of Karneios Apollo (possibly where Pera Kalamitsi now stands, a short distance northeast of Kalamata) where there was a spring.  Floor mosaics of the Roman period, Kalamata’s Archaeological Museum Sherds of ceramic tiles decorated with floral designs have been found there, dating from the Late Archaic period, along with a funerary urn of the Geometric period (8th century BC), containing a bronze pony and bronze clasps. However, there is no reference to the temple of Athena Nedousia seen by Strabo in the 1st century AD. Traces of the ancient town consist of foundations of walls and a tower from Pharai’s classical fortification, about 250 meters south of the castle, ancient inscriptions carved on rocks (mouthof the Nedon, at Lithomeno Fidi), pottery sherds of the Late Helladic III period (1200-1100 BC, on the south side of the hill, on which the castle stands), a carved gravestone of the same period (hill of Turles), ceramic sherds of commemorative tiles from the Archaic and Classical periods (on the same hill) as well as a commemorative inscription of the 1st century AD dedicated to Zeus (exhibited in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens).  Octavianus Augustus Byzantine era

Traces of human habitation have been found at the acropolis of ancient Pharai dating from both the Late Roman and the Early Byzantine era – a time when the region’s importance was somewhat diminished. The Byzantines used this geographical area as a base and bastion, particularly after the 7th century. In fact, according to all indications, the fortress of Pharai played an important part in dealing with the Slavs, who arrived in the region in the second half of the 7th century, during which the Byzantines were extending their rule from the coast towards the Messinian hinterland. In fact, as they failed to occupy the Pharai region, the Slav populations settled first in ancient Kalames, renaming it Yiannitsa (today’s Elaiohori), in Selitsa (Verga) and the mountains of the western Taygetos range, only to be wiped out finally in the middle of the 9th century. There is scant historical evidence for the period between the 6th century (the rule of Emperor Justinian), when the last reference to Pharai occurs, in the Synecdemus of Hierocles, and the 10th century, when the first reference to the town of Kalamata appears.  Exhibits of

the Roman

collection,

Archaeological

Museum of

Kalamata These documents include texts showing the early appearance of a royal road, coins dating from the 8th and 9th centuries, a rare bronze coin depicting the Emperors Constantine VI and Irene the Athenian (780-790 AD) from Aghios Floros and another bronze coin depicting Leo VI (886-912 AD), from Kalamata. The first written evidence of the town’s existence is found in the Life of Saint Nikon Metanoeite (written in 1142), which refers back to the period 968-998. It calls the city Kalom(m)ata or Kalam(m)ata. This confirms the strategic position and the importance of a settlement within the theme of the Peloponnese, that had its seat in Corinth and came under the jurisdiction of the Metropolis of Patras. The settlement was already the capital of Messinia and spread south and east of the Kastro. In the mid-12th century, Kalamata had already become quite important; it had a monastery with links to Sparta (probably the monastery in the Kastro, referred to in the Chronicle of Morea, written in the 14th century and which describes events in the 13th century). It was a hub on the roads linking the mountains with the southwest coast of the Peloponnese.  Archaeological findings prove that the

Byzantines were in the area long before

Saint Nikon Metanoeite (end of 10th

century). The underground section of

the Church of Saint Haralambos, as

well as sections of the Kastro, also

indicate this. The earliest sections of important religious monuments such as

Aghi Apostoli, Aghios

Haralambos, Aghios

Constantinos at the Kalograion

Monastery and Aghios

Dimitrios in Turles also date from the same period (11-12th centuries).

Frankish conquest

According to the sources, Kalamata’s history actually begins after 1205, that is after its conquest by the Franks, under the leadership of Geoffroy de Villehardouin and Guillaume de Champlitte. The latter was nominated ruler of the region. After his death (1209) and a somewhat turbulent period, he was succeeded by Geoffroy de Villehardouin, who retained sovereignty over the barony of Kalamata and generally the principality of Achaea until his death in 1218.

He was succeeded first by his eldest son Geoffroy II (1218-1245), who concentrated on the principality’ s administrative and economic organization. He was followed by Guillaume II (1245 - 1278), called Kalomatis as he was born in the Kastro of Kalamata. In 1259 Guillaume was defeated at the Battle of Pelagonia by the Emperor of Nicaea, Michael VIII Palaiologos and imprisoned for two years. In exchange for his freedom, he surrendered the fortresses of Mystra, Monemvasia, Geraki and Megali Maina, also taking an oath of subservience. After 1262 the Franks’ power began to wane due to the expansion of the Despotate of Mystra and Venetian sovereignty over the fortresses of Methoni and Koroni. After Guillaume’s death in 1278, the rule of the fortress of Kalamata did not pass to his widow Anna (Agnes) Komnine or his daughters Isabelle and Marguerite, but to the French King of Naples (Lower Italy and Sicily) Charles I of Anjou and then his heir Charles II.  Aghi Apostoli In 1289, Charles II ceded the principality and Kalamata to Isabelle and her second husband Florent d’Hainaut. In 1293 the Slavs of Yiannitsa conquered Kalamata and raised the Byzantine symbols, but the city once again fell to the Franks after a betrayal by the military governor of Mystra, G. Sgouromallis. After the death of Florent (1297), Isabelle gave her daughter Mathilde in marriage to Guy II de la Roche of France, and the city of Kalamata as her dowry. The town thereby came under the Duchy of Athens. Mathilde retained sovereignty over the city even after marrying a second time. She was succeeded by John, ruler of Gravina (1318-1333), Catherine de Valois (1333-1346) and the Florentine banker N. Assagioli, who created the castellania of Kalamata with the inclusion of some of its surrounding villages. His adopted son Angelos (later the archbishop of Patras) succeeded him, then Marie de Bourbon and Basque mercenaries. It was another emperor, C. Palaiologos, who brought an end to the Frankish rule in the early 15th century, including the town in the Despotate of Mystra.  Aghios Dimitrios in Turles In later Byzantine years, Kalamata’s strategic position at the head of the Messinian gulf led to its rapid development and made it the object of contention between the brothers D. and Th. Palaiologos. It was eventually conquered by Mohammed II in 1470, during the First Venetian-Turkish War (1463-1479). Turkish – Venetian Occupation

The conquest of the region by Mohammed II marked the beginning of the First Turkish Occupation (1470-1585), during which the Turks divided Messinia into two pashalik, with Kalamata included in the pashalik of Koroni.  Coin of

Villehardouin An attempt to throw off the Turkish yoke appeared almost right after the conquest, but met with failure; the final battle took place under the walls of Kalamata. About two centuries later, during the Second Venetian-Turkish War (1645-1669), the allied forces of Maniots and Venetians led by Francesco Morosini temporarily liberated Kalamata, in 1659. The town sustained considerable damage before once more falling to the Turks. The Venetians under Morosini took Kalamata once more in 1685, again with support from the Maniots. The Kastro sustained major damage and during the Second Venetian Occupation (1685-1715) an attack by Maniots convinced Morosini and the Venetians not to demolish it but to restore it, work that was completed in 1693. During the Second Venetian Occupation, reference was made to the presence in the town of a large military force for its defense.  Princess Izambo,

by A. Terzakis.

The story takes

place in

Kalamata during

the Frankish

conquest. During the same period, Kalamata was one of the 16 regions of Messinia, whose first capital was Koroni and then Methoni. Already in the early 17th century after the Turkish conquest of Monemvasia, the united metropolis of Monemvasia and Kalamata had transferred its seat from the former to the latter. At that time, the town’s inhabitants (numbering 1,362 in 1700) were growing wheat, grapes, olive and mulberry trees (for the silkworm industry) and also raising livestock. Their homes were poor, with roofs of slate. The first rudimentary schools opened during this period.  Constantine

Palaiologos

depicted by

Fotis Kontoglou During the Second Turkish Occupation (1715-1821), consolidated during the last Venetian-Turkish war (1714-1718), the town was the most densely populated of all the 24 vilayet that comprised the pashalik of Morea and one of its most flourishing commercial centres. At the same time, there were fewer Maniot raids (one is mentioned in 1723) and there was in fact trade between Mani and Kalamata. Despite the plague outbreak of 1717-1718, the population had risen to 2,500 in 1820. In 1767 Georgios Papazolis, a Greek officer in the Russian army arrived at the fortress of the Kalamata ruler Panayiotis Benakis. Their meeting led to the uprising of 1769-70, known as the Orloff revolt, when Kalamata was seized by Maniots and Russians, followed by a catastrophic and bloody counter-attack by Albanian mercenaries working for the Turks.  Fr. Morosini After the Russians fled and the Greeks were slaughtered, the Albanian mercenaries appeared in the area, later to be ousted by Capudan Pasha Hassan in 1779. In the final years of Turkish occupation Kalamata, now a market town, was a hub for the trade in farm and livestock produce of the hinterland (wheat, cotton, wine, silk, dried figs, olive oil, leather, wool and cheese). Ships sailed from its port with cargos of exports to Smyrna, Constantinople, Alexandria, Marseilles and northern Italy. The French had founded branches of their trading companies there and in 1721 set up a vice-consulate, indicating that Messinia was part of the zone of interest for Western commercial agents.  The battle of Kalamata, fought

between Venetians and Turks,

with the participation

of Maniots (1685), in an

engraving by the Venetian

mapmaker V. Coronelli

(18th century) Powerful landowning and merchant families had emerged, creating a commercial aristocracy in the town, assuming a political and administrative role. The 1821 War of Independence

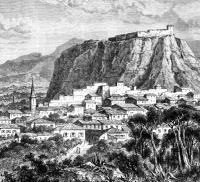

The region around Kalamata, along with Mani, played a major role in the preparation for the War of Independence and in its early stages. Moreover, several local notables were early members of the Philiki Etairia (“Friendly Society”, founded to liberate Greece from the Turks).  The fortress of Kalamata at

the end of the 17th century in

a drawing by the Dutch artist

O. Dapper In January 1821, Theodoros Kolokotronis arrived in Kardamyli and the next month the Turks, having become aware of the revolutionary spirit that was brewing, sent several local notables and prominent clerics to prison in Tripoli. They even forced the latter to write and sign a text condemning any future uprising. This did nothing to quell the Greeks’ revolutionary fervor. Moreover, in the middle of March a ship docked in Almyro bearing munitions sent by the Philiki Etairia branch in Smyrna. Meanwhile the resourceful and passionate Papaflessas ensured that any hesitation on the part of Petrobey Mavromichalis was overcome. On March 23, revolutionary forces of Maniots led by Petrobey Mavromichalis, other Maniot captains and Theodoros Kolokotronis arrived outside Kalamata, approaching the town from hills to the northeast, from the monastery of Velanidia, along with other forces led by Papaflessas and Anagnostaras. The previous day a force of 2,500 Maniots had arrived in the town led by Petrobey’s son Ilias and his brothers Antonis and Yiannis, pretending to protect Kalamata’s voivod, Suleiman Aga Arnaoutoglu. Unable to react, Arnaoutoglu was forced to surrender without a struggle, on the condition that the Turks’ lives would be spared.  Pharai, today’s

Kalamata,

lithograph by

Otto von

Stackelberg, 1813 On the afternoon of March 23, the Greek forces led by Petrobey Mavromichalis, Theodoros Kolokotronis, Papaflessas, Nikitaras, Anagnostaras, Mitropetrovas and many other chieftains from the surrounding southwestern Peloponnese met in Aghi Apostoli Square on the banks of the Nedon River (prevalent view), or in Aghios Ioannis Prodromos (recent indications), where a church service was held. After the town was liberated, divisions of Greek fighters headed for Skala, Messinia and to Karytaina (led by Theodoros Kolokotronis), to Tripolitsa (with Papaflessas, Anagnostaras and Kyriakoulis Mavromichalis) and to Koroni and Methoni. Maniot chieftains and local elders stayed in the town to set up the first revolutionary government of liberated Greece, the “Messinian Senate”.  Petrobey Mavromichalis with the Greek rebels

of Messinia, in a painting by Peter von Hess

(Munich Stadtmuseum) The town was threatened on August 23 when 10 Turkish ships appeared offshore, but the presence of a small force of Maniots and the first divisions of the newly established Greek regular army prevented the Turks from landing. Civil conflict had broken out in the army camp and so when Ibrahim landed in Methoni in February, 1825, there was no resistance. Ibrahim swept onward from Kremmydia (April 7) and Maniaki (May 20) and seized Kalamata on May 28.  The bust of Papaflessas in March 23 square A year later (June 22, 1826), Ibrahim was roundly defeated by Maniots in the Battle of Verga. He was then defeated at Navarino (October 20 1827). After a French expeditionary force led by General Nicolas Maison landed in the area, Ibrahim withdrew from Methoni on September 28, 1928. More recent history

Liberation found Kalamata in ruins, its olive groves destroyed by fire and its livestock virtually non-existent. Until then, it had been a fortified market town with a mainly administrative role within the Turkish eparchies. From the time of the Independence War until the end of the 19th century, it became a flourishing coastal town with considerable commercial activity. In 1831 Kalamata saw the uprising of the Mavromichalis clan, who rose up against Ioannis Kapodistrias, seized the town and ousted the Kapodistrian services and authorities.  National

Assembly in

Kalamata –

The glory

of the

assassinated

Patriarch

Grigorios V,

a painting

by Leo von

Schwandhaller,

(Munich

Stadtmuseum) Another trial for the city was the great flood of 1839, a terrible earthquake in 1844 (or 3), and the uprising of 1848, when G. Perrotis at the head of a force of 700 men, seized the town in a move that, he claimed, was linked to the democratic uprisings in Europe that year. The revolt was put down and its instigators prosecuted by the regime’s troops. In 1833, the eparchy of Kalamon had already been established, with Kalamata (Kalamai) as its capital. In 1835 King Otto’s Bavarian administrators had declared the town the seat of the prefecture (instead of Kyparissia). The municipality of Kalamata (Kalamai) was set up on the same year. A major factor in the post-independence growth of the town was the trade in farm and manufacturing products from the surrounding Messinia countryside and other nearby areas in the southern Peloponnese. These included figs (the most stable export product until the 1950s), oil from the famous Kalamata olives, silk and raisins.  Statue of Theodoros Kolokotronis in Kalamata’s central square Olive cultivation developed at the end of the 19th century and the first olive presses were set up after 1875, as additions to exiting structures (silk factories and flour mills). The silk was the main product of the people of Kalamata since the time of the Turkish occupation and a major export until the First World War. In fact, in the mid-1870s Kalamata had become the main silk manufacturing center in the new Greek state and its prize-winning silk scarves and fabrics were sold everywhere.  After the town was

liberated, a thanksgiving

service was held in the

church of Aghi Apostoli

(prevalent view), in which

24 priests and abbots

blessed the fighters’ flags

and gave them the oath of

the liberation struggle.

Pictured is a representation

of the doxology,

by E. Drakos The town also owed its first experience of industry to silk, as early as 1850. At the end of the 19th and the early 20th century, there were 500 silk looms operated by manufacturers or private individuals. In 1933, when the Stasinopoulos factory closed, it marked the end of an era. The famous workshop of the Kalograion Monastery was a decisive factor in the development of the silk weaving industry, as its training program laid the foundations for the local home industry. In 1860 there were 108 small merchants, 8 major merchants, 225 landowners and 800 “industrialists” (craftsmen, tradesmen).  In Kalamata in August, 1821, three issues of the

newspaper “Salpinx Elliniki” (“Greek Bugle”) were

published, the first newspaper printed and distributed

in liberated Greece. Dimitris Ypsilantis had appointed

Theoklitos Farmakidis as its “supervisor and publisher”. The town’s population growth and intellectual activity occurred at a similarly fast pace. In 1879 the population stood at 7,069; by 1889 it had grown to 10,696 and by the end of the 19th century to 15,000. In 1856 Messinia, the town’s first weekly newspaper appeared. Some years earlier elementary schools of boys and girls opened, then the “Greek School” or “Scholarcheio” (1835), and in 1861 the first high-school of the city and district. At the end of 1860 the first private school opened for basic education, followed by two more in 1871 and then a School for Poor Children, a Girls’ College and then in the second decade of the 20th century, the Arsakeio City School. The construction of a port was an important development for the town. Begun in 1882, it was completed in 1901. Before then, goods were exported – with difficulty it is true - from the gulf of Almyro (seven kilometers southeast of Kalamata) and from rudimentary installations on the beach or on barges, but only in summer.  Kalamata and

the frankish

castle (1868),

drawing

Th. Weber

from a sketch

by Henri

Belle Also important was the foundation of the Nea Kalamai district in 1860, at the eastern end of the beach, the construction of the road from the Kastro to the beach and the railway line to Athens, as well as the coming of electric light. In the beginning of the 20th century the city continued to flourish. In fact, from 1900 to 1920, the port was in full swing and had merged with the town and a new market had grown up around the wharf. These developments led Kalamata to be called the «Marseilles of Morea». In 1914 the Greek refugees from Asia Minor arrived in town, but the largest waves of them arrived in 1922. Most of them settled on the fringes of town, mostly along the coast to the west and east (Analypsi, Kordias, Ano Paralia, Aghia Triada, Aghios Constantinos and other districts). During the first decades of the 20th century new industrial units opened, such as silk mills, distilleries, soap industries, ice making industries and tanneries.  Raisins were Kalamata’s main export crop until

the crisis in the sector in 1890. Afterwards the

grapes were sent to the town’s famous wine

and spirit manufacturers. In this picture,

labels from the D. K. Stefanouris spirit

factory (that operated from 1892 to 1980) (photo: GSA archive of Messinia). The flooding of the River Nedon in 1924 was a major disaster for the town, which continued to flourish. The development of the city was followed by the development of the labour movement, the presence of which was powerfully declared with the riot of port workers in 1934 that was put down by the army, resulting in six deaths and 13 injuries among the workers. In April 1941, the town was occupied by German troops, following intensive bombing and a battle between the invaders and retreating British army divisions. In February 1944, the German army executed 149 Greek patriots in reprisal for a guerrilla ambush. In September of the same year, however, the town was liberated. After the war the final countdown for the town’s industries began, a tendency that will continue particularly after 1960, during which the town entered a period of decline. The last tragedy for Kalamata, (in 1959 was officially renamed Kalamata from Kalamai), was the massive earthquakes of September 13-15, 1986. Since then, there has been a major attempt of reconstruction, which forms the city of today.  Raisins were Kalamata’s main export crop until

the crisis in the sector in 1890. Afterwards the

grapes were sent to the town’s famous wine

and spirit manufacturers. In this picture,

label from N. G. Kallikounis, that has been

operating since the mid-19th century until

today (photo: GSA ∞rchive of Messinia). |